Editor’s Note: This story was originally published on 5 July, and has been republished on 9 July with a correction made to TrueNat’s limitations. The story now reflects, as per the ICMR advisory dated 19 May 2020, that TrueNat is a comprehensive assay for screening and confirmation of COVID-19 cases.

The scale and accuracy of ongoing COVID-19 testing in India are in a gradual state of evolution, with new and improved kits developed by biotech companies worldwide coming into existence. Recently, the Indian Council of Medical Research recommended ELISA (short for ‘enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay’) for labs to test for COVID-19.

ELISA falls under one of two broad categories of testing being used by every country around the world to stay on top of their pandemic control:

- Antibody testing (a.k.a serological testing)

- Antigen tests

- Polymerase Chain Reaction-based tests (like RT-PCR and TrueNat)

While some are more reliable than others, no single test is 100 percent accurate. There are key differences between them – in the way they work, but also their advantages and limitations, which are unique to each.

How antibody or ‘serological’ tests work

Antibody testing (or serological testing) is an examination of proteins in the bloodstream, to find out whether an individual has been infected with COVID-19. An infected person will have specific antibodies to pathogens they have been exposed to. The immune system produces antibodies as part of a larger process to defend itself from an infection.

That said, antibody tests may not be able to show whether the virus is currently infecting the body. Unlike a nasal or throat swab test, which looks for genetic signatures of the virus in the body, an antibody test looks for traces of the body’s response to the virus.

Antibodies are abundant in the blood, so a sample of blood is collected by either a finger prick or a blood sample drawn with a needle. Two specific antibody types are sought out in an antibody test:

- IgM antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, which develops early on in an infection.

- IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, which are mostly found after someone has recovered from the infection.

Antibody testing has many uses in a pandemic

First and foremost, antibody tests can give authorities and individuals clarity as to their COVID-19 status.

At the community and national levels, widespread antibody testing gives researchers and authorities estimates of the rate of infection (how quickly the virus is spreading in a population), and how fatal COVID-19 is. This data informs important decisions around testing, prevention, and treatment of COVID-19.

Along with other information collected from patients in hospitals, antibody testing can also offer information on what factors affect the severity of infection, and why some people are more severely impacted than others.

Vaccines are developed under the principle that a shot imitates a mild case of the infection itself, and once injected, it helps the immune system mount a stronger attack against a pathogen when it does attack. This offers some protection from a full-scale attack of COVID-19. Antibodies are made more quickly and copiously as part of this vaccine-enabled response.

Limitations of antibody testing

Margin of error: Antibody tests are important for establishing who has had the virus, especially because a percentage of people infected seem to show no symptoms. An antibody test can give results in under an hour. For instance, the ICMR-approved antibody testing kits show results within 30 minutes. The test can be used 7 to 10 days after someone is infected, but do have a larger percentage of error than swab tests.

Antibody tests that look for IgM antibodies are usually rapid finger prick tests that can deliver results in under 20 minutes. But IgG tests require a blood sample to be sent to a lab – a process that could take a week to deliver results. IgG tests are more reliable than IgM rapid tests, but don’t reveal as much information about someone’s COVID-19 infection.

False negatives and false positive: The many diagnostic kits in circulation currently are a necessity – but they are also products of fast-track approval and developing research into COVID-19, where the priority is public health demand and speed.

Considering the developing nature of ongoing COVID-19 research, there is no assurance of quality, or guarantee that a test result is 100 percent accurate. Some kits will perform better than others.

There may be cases where exposure to COVID-19 isn’t followed by the production of antibodies in an individual, showing up as a ‘false negative’. Tests that aren’t of high-quality may also show a ‘false positive’ if an individual has another, very similar virus in the body.

Currently, ICMR is the authority recommending the most suitable kit for widespread antibody testing after making these due considerations. A report in the Hindu highlights multiple instances of quality assurance of testing kits being severely lacking.

Overwhelming inaccuracies in testing asymptomatics: There have been a few dozen studies that measure the accuracy of antibody tests compared with a reference standard to detect an ongoing or past COVID-19 infection. In a review of these studies, authors found that antibody tests one week after the first symptoms appeared only detected 30 percent of positive COVID-19 cases. The accuracy increased in the second week, with 70 percent of cases detected. It was highest in the third week, with over 90 percent of cases detected.

We know that it takes anywhere between 1-3 weeks to develop antibodies after symptoms occur, which makes the test as good as a coinflip in people who don’t show symptoms.

False sense of security: While this isn’t a challenge of antibody tests exclusively, it is one that needs to be considered. On getting a positive COVID-19 antibody test, a person may very well think that having COVID-19 antibodies gives them immune to the virus and won’t catch it again. There is currently no evidence to suggest that people who have recovered from COVID-19 are immune to catching it again.

Even if studies show antibodies are found to offer immunity, it is difficult to establish how much antibody is needed to offer this protection, or how long the protection might last. Scientists world over are carrying out research studies to answer these questions.

There are also rapid tests in use in some countries to diagnose active COVID-19 cases, since the tests would be much quicker and less invasive than the current swabs. The two kinds of rapid tests being used in India currently are the antigen test and RT-PCR test.

How antigen testing works

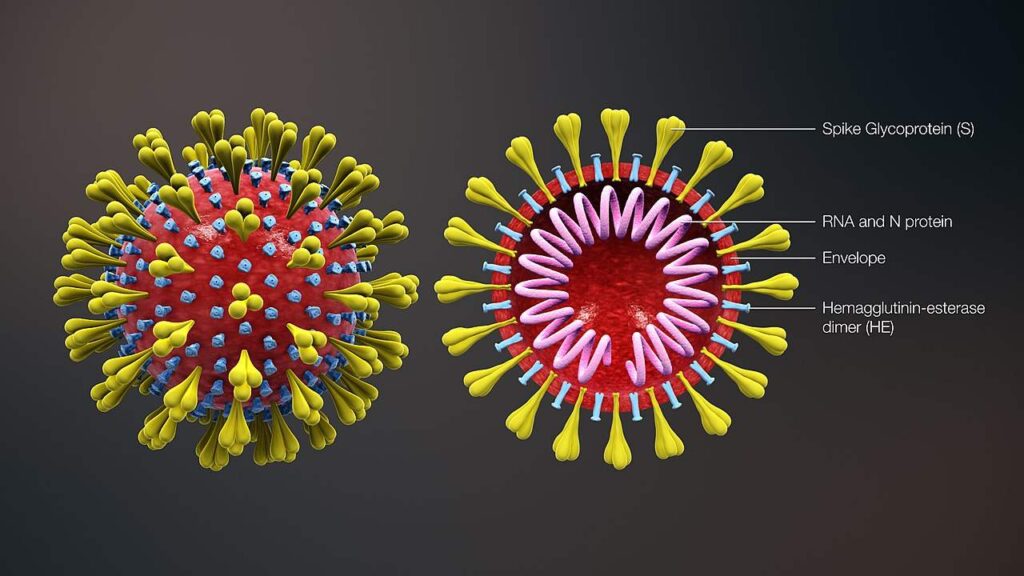

Antigen tests seek out specific proteins only found in the virus, which the body’s immune response recognises as ‘foreign’. Most COVID-19 antigen tests target the ‘spike protein’ that studs the surface of the coronavirus.

A swab from the nose is collected for this test, where there’s a high likelihood of virus particles being present. The swab is then dipped in a solution that inactivates the virus, and then transferred onto a test strip. The test strip houses antibodies that bind to coronavirus proteins and hold them in place as the fluid spreads.

If the sample is positive for coronavirus, colored lines will show up on the paper strip in 15-20 minutes.

Antigen testing has some key advantages

One of the major advantages of using antigen is that it reduces the burden of relying on just RT-PCR tests to identify COVID-19 patients.

“Antigen testing is useful because even if it’s less sensitive, it is rapid and the results that are positive will be positive,” Dr Gagandeep Kang, executive director of the Transnational Health Service and Technology Institute, told thePrint in an interview. “So, patients who test positive can get into isolation faster.”

Antigen tests remove about half of the positives from the testing load, she added.

Antigen tests are also inexpensive compared to RT-PCR, costing around Rs 450 per test.

Limitations of antigen testing

An antigen test can only reveal whether a person is currently infected with SARS-CoV-2. Before or after the infection has passed, antigens won’t be present.

Since antigen testing doesn’t involve any processes of amplifying the virus or its genetic material, a swab sample may have too little antigen to be detected. This could produce a false negative result. As a precaution, a negative test should be followed up by the more accurate RT-PCR test, to confirm a true negative for COVID-19.

Accuracy is the single largest problem with antigen tests, which are much less sensitive than RT-PCR as a diagnostic tool.

How a PCR test works

A PCR test is a widely-used, highly sensitive test that seeks out traces of genetic material from a specific pathogen, if the pathogen is present in the body. The technique is a powerful diagnostic tool that can identify both DNA or RNA from specific microorganisms, irrespective of whether they are bacteria or viruses.

A PCR can capture a specific gene from genetic material (DNA or RNA) in a swab sample, and multiply it through a series of chemical processes so it can be detected using fluorescent dyes.

RT-PCR, a variation of the PCR test

The version of PCR testing used to detect viruses like the COVID-19-causing SARS-CoV-2 is called RT-PCR (reverse-transcription PCR).

While some viruses have only DNA, others like SARS-CoV-2, only contain RNA. Viruses infect a healthy cell and hack into the natural machinery that cells use to process our own RNA, so the virus particle can multiply and survive. Once inside a cell, the virus uses its RNA to take control of the cell’s machinery and ‘reprogramme’ the cell into a virus-making factory.

To detect an RNA virus like SARS-CoV-2, scientists use an enzyme (reverse transcriptase) to convert the virus’s RNA into DNA, in a simple and widely-used one-step process called ‘reverse transcription’. This allows a single molecule of DNA to be amplified exponentially (millions of times), which is the main goal of the PCR process, so even virus particles in single digits can be detected in the final result.

An RT-PCR test is considered very reliable because it can detect even a single virus particle in swabs taken from inside the mouth or nose, where the virus particles are most prevalent.

Advantages of RT-PCR testing

Swift, sensitive and specific: There are real-time variations of the RT–PCR technique that are quick, super sensitive, and specific. They can deliver a reliable diagnosis in three hours. That said, the process on average takes around eight hours to produce a conclusive result.

More accurate, less prone to contamination: Compared to other methods to isolate and detect viruses, RT–PCR is much faster and less likely to be contaminated or cause errors during the testing process. This is because the test – start to finish – is carried out in an enclosed tube, inside a specialised, automated machine.

Real-time RT-PCR continues to be the most accurate method we have to detect the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Severity of infection can be estimated: A standard real-time RT–PCR set-up usually goes through 35 cycles, which means that, by the end of the process, around 35 billion new copies of the sections of viral DNA are created from each strand of the virus present in the sample.

Limitations of RT-PCR testing

Only detects ongoing infection: The main limitation of RT-PCR testing is that it cannot be used to detect a past infection with SARS-CoV-2, which is important for understanding the development and spread of the virus, as viruses are only present in the body for a specific window of time.

Other methods are necessary to detect, track and study past infections, particularly those which may have developed and spread without symptoms. Once you have recovered, the virus is eliminated and these tests can no longer tell if you’ve been infected. This creates significant uncertainty, especially if someone has self-isolated due to mild and unclear symptoms.

Requires specialised equipment, training: Unlike antibody testing, which requires a kit and medical/paramedical personnel trained in using the kit, RT-PCR testing needs specific instruments in a laboratory, which makes it more time-consuming. Even if the test itself takes just a few hours, the process of collecting and labeling samples, transporting them to a lab, and processing the samples in bulk ensure that it is days before the results from a single sample are known.

Portable, rapid RT-PCR machines are at the cutting edge of diagnostic technology, and often require specialised training to ensure the machine isn’t misused, which requires some level of expertise and training. Tests are only now being developed and made available for these advanced instruments.

Quality control is not a guarantee: In a pandemic, the use of even very accurate diagnostic tools is more error-prone than daily diagnostic tests. RT-PCR, while a revolutionary tool in diagnosis, can also be easily misused or misinterpreted. It depends on a reliable existing DNA sample of the virus, as a reference, to find the pathogen in a test. It is also sensitive enough to pick up on contamination as a false positive.

Back when the outbreak first began to spread in India, the National Institute of Virology in Pune was the only laboratory testing for COVID-19. Today, there are 1,000. The validity and accuracy of a test depend entirely on the laboratory’s quality. The Hindu reports multiple instances of private and public testing labs (including quality assurance labs) returning false positives at an alarming rate. Experts have called for internal quality control and external quality assessment as an urgent requirement if PCR testing is to be considered reliable.

Quantity meets quality with TrueNat testing

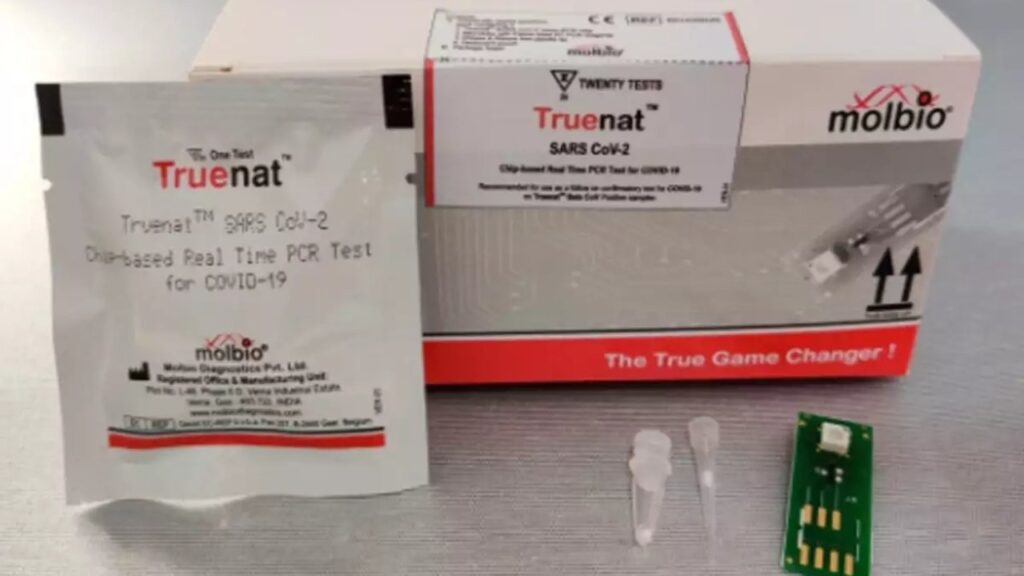

Most modern PCR tests can detect a wide range of pathogens in real-time, with results visible as the chain reaction is underway. TrueNat is a chip-based, portable RT-PCR machine, originally developed as a portable diagnostic tool for tuberculosis by Goa-based startup Molbio Diagnostics.

The device is on its way to becoming one of the main diagnostic tools for COVID-19 as India looks to expand its testing capacity. It is the fastest available PCR-based technique recommended by ICMR till date.

The latest versions of the TrueNat machine can detect an enzyme (called RdRp) found in the RNA of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. The ICMR has ruled that these tests can be treated as a confirmation for the presence of the coronavirus.

TrueNat can return results faster time than the standard RT-PCR tests, according to Sriram Natarajan, CEO of Molbio Diagnostics.

In a letter shared by ANI dated 4 July, ICMR has advised private laboratories in states and Union Territories that intend to use TrueNat for COVID-19 testing to apply for NABL accreditation immediately, to ensure reliable results.